美国卡托研究所网站3月18日文章,原题:对不起,工会,美国造船业的困境与中国无关 美国钢铁工人联合会和其他工会上周提交一份请愿书,要求美政府对中国采取行动——他们将美国商业造船业的空心化归咎于中国的“扭曲性”措施。考虑到美中的敌意和大选年的政治因素,请愿的时机可谓“恰逢其时”。两名参议员已宣布支持,拜登和美国贸易代表也在社交媒体上强调了这个请愿。然而,这种抱怨是虚伪的,也与历史不符,且最重要的是,是错位的。

2024年LNG接收站和产业上海大会将于2024年4月23日-24日举办

2024年造船厂地图龙年新版免费赠送的恐龙悍狼式正式发布开始赠送

请愿书承认,一系列因素解释了美国商业造船业数十年的衰退,但又称“自2000年以来,行业受挫主要是由于来自中国的不公平竞争”。这种对历史的解释非常牵强。实际上,即使在1981年取消补贴前,美国造船业的表现也很一般。从1951年到1981年,美国造船厂在全球船舶交付量中的占比仅有两次超过5%,平均每年交付18艘船,远远落后于法国、瑞典、英国和德国,更别说日本了。美国造船厂长期缺乏竞争力,自1960年以来就没建造过用于出口的船,几乎全部订单都不是来自竞争激烈的国际市场。早在中国崛起前,美国就已沦为全球造船市场的边缘角色。1990年,中国的造船产量仅占全球的2.5%,当中国开始在国际市场上大展拳脚时,美国的造船厂早已退出市场。

关于中国补贴影响美国造船厂命运的说法,同样经不起推敲。美国制造的远洋商船价格比海外制造的至少高出3倍。即使取消中国所有补贴,美国造船厂仍将被挤出国际市场。

为对华施压,请愿书呼吁对中国制造的船只停靠美国港口征收新费用,并将所得收入捐给美国商业造船振兴基金。该基金将用于加强美国补贴计划——这是事实上的关税,用于资助已被证明对重振美国造船业无效的做法。这种抢钱并不令人意外。但工会对美国航运公司频繁光顾中国船厂进行维修视而不见,就有点令人吃惊了。若惩罚中国船厂是目的,那此类维修似乎就是关税的针对对象。

针对中国采取行动,无疑具有政治吸引力,但这对阻止美国商业造船业的衰退毫无帮助。美国造船业无力参与国际竞争,并不是近几十年来中国行为的产物,是极端的保护主义扼杀了美国造船业的竞争火种。美国不应在补贴问题上扔石头,而应先检查一下自己的玻璃房子。(作者柯林·格拉鲍,乔恒译)

Sorry Unions, China Isn’t Responsible for US Shipbuilding Woes

By Colin Grabow

Last week the United Steelworkers and other unions filed a Section 301 petition seeking US government action against China over its employment of subsidies and other market‐distorting measures that they blame for the hollowing out of the US commercial shipbuilding industry. Given US‐China animus and election‐year politics, the petition’s timing is auspicious. Indeed, two senators have already announced their support and both President Joe Biden and US Trade Representative Katherine Tai have highlighted the filing on social media.

The complaint, however, is hypocritical, ahistorical, and—most of all—misplaced. While there is no doubt that China engages in market‐distorting practices, they have little explanatory power for the US shipbuilding industry’s enfeebled state.

In the unions’ telling, the United States was one of the world’s leading shipbuilders in the post‐World War II era until the 1981 demise of construction differential subsidies that paid up to half the cost of US‐flagged ships used in foreign trade (ships operating domestically were ineligible). Although the petition later concedes that an “array of factors” explains US commercial shipbuilding’s decades‐long decline, it argues that “headwinds facing the industry since 2000 have been due primarily to unfair competition from China.”

This is an incredibly strained interpretation of history.

As I’ve previously documented, the US shipbuilding record even before the defunding of construction differential subsidies was thoroughly mediocre. From 1951 to 1981, US shipyards’ share of global ship deliveries only exceeded 5 percent twice (1953, 1954) and most years did not exceed 3 percent.

The 18 ships per year delivered on average by US shipyards during this period trailed the shipyards of France (28), Sweden (41), and both the United Kingdom and Germany (80+ each) by significant margins and were dwarfed by those of Japan (270).

While the petition points out that US shipyards in 1975 had “more than 70 commercial ships of 1,000 gross tons or more on order (emphasis added),” their actual deliveries that year did not crack the global top ten. That’s no surprise given their long‐standing lack of competitiveness, with no vessels built for export since 1960. Rather, US commercial shipyards’ orders consisted almost exclusively of subsidized vessels and those required to be built by the Jones Act—not the competitive international market.

Far from a shipbuilding leader, the United States had been relegated to a peripheral role in the global shipbuilding market long before China’s emergence. By the time China—responsible for only 2.5 percent of global shipbuilding output in 1990—started flexing its shipbuilding muscles in the international market, US shipyards had already made their exit. China’s rise has come at the expense of other major shipbuilders, such as those in Japan, South Korea, and the European Union—not the United States.

Claims that Chinese subsidies have had any bearing on the fortunes of US shipyards in recent decades, meanwhile, similarly fail to withstand scrutiny. US‐built oceangoing merchant ships can cost at least 300 percent more than those built overseas. China’s shipbuilding subsidies, however, have been estimated to only reduce their shipyards’ costs by 13–20 percent. Significant to be sure, but an amount that pales in comparison to the vast gulf with US prices.

Remove all Chinese subsidies and US shipyards would very much remain frozen out of the international shipbuilding market.

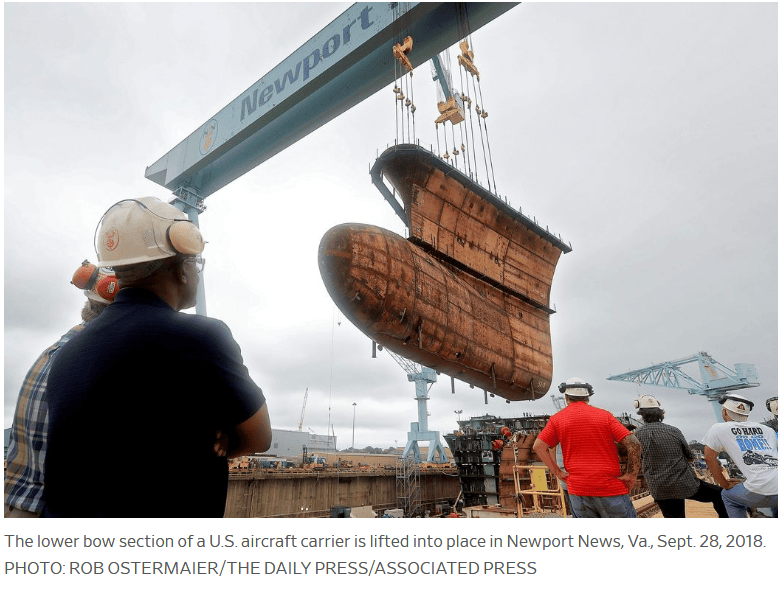

ship

There’s also the small matter that the US government is itself an avid practitioner of shipbuilding subsidies. Not only does the United States require that vessels used in intra‐US commerce be domestically constructed to comply with the 1920 Jones Act—a significant giveaway to the shipbuilding industry—but it also attempts to promote domestic shipbuilding via federal loans, tax advantages, and direct grants. State and local governments dispense additional goodies. Philly Shipyard, for example, has received over $200 million from the Pennsylvania state government and has a $1 per year lease.

Notably, US shipyards helped torpedo a 1990s agreement to rein in international shipbuilding subsidies. They’ve not just taken advantage of subsidies but have helped perpetuate their worldwide use.

This US affinity for subsidies is also reflected in the petition’s proposed actions. To pressure China over its shipbuilding practices, the petition calls for leveling a new fee on US port visits by Chinese‐built vessels with proceeds going to a “US Commercial Shipbuilding Revitalization Fund.” This fund would be used to beef up existing US subsidy programs and resurrect the construction differential subsidy program—in other words, a de facto tariff to bankroll a playbook that has proved ineffective in revitalizing US shipbuilding.

The money grab is no shock. It is, however, somewhat surprising that the unions turned a blind eye to US‐flag shipping firms’ frequent patronage of Chinese shipyards for repair work. If punishing Chinese shipyards is the goal, such work would seem a logical candidate for higher tariffs. Or, better yet, why not eliminate the tariff for work performed in shipyards outside of China to divert business away from the country?

Although the pursuit of action against China over its market distortions is no doubt politically attractive, it will do nothing to arrest US commercial shipbuilding’s long decline. The industry’s inability to compete internationally isn’t a product of Chinese perfidy in recent decades but a reality that dates back to the 19th century.

The constant in this ongoing saga of US failure is not subsidies by China or any other Asian country but extreme levels of protectionism that have smothered US shipbuilders’ competitive fire. Instead of casting subsidy stones, US policymakers should first inspect their own glass house.